Trapped in the algorithm of our own reflection.

Robert Del Naja of Massive Attack, Adam Curtis & Mario Klingemann team up for an audio-visual masterpiece to break the nostalgia of the 21st century.

Article published in Italian on cheFare the 21st March 2019.

On January 28, 2019, in Glasgow, Massive Attack kicked off the tour for the 21st anniversary of Mezzanine, a seminal album not only for the enthusiastic audience and critical acclaim, but also for what it represents in the band’s history, that is a painful and hazardous fracture (due to some creative conflicts, during the 1998 tour they parted with band member Andrew Vowles) in distancing themselves from that “Bristol sound” they had championed.

The idea behind Mezzanine XXI stems from a reflection on the events that have unfolded since 1998, and how the gloomy and ground-breaking atmospheres of the legendary album became prevalent over the past twenty years.

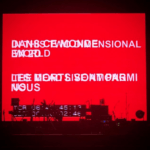

A careful analysis of these sounds takes form through the deconstruction of Mezzanine and a new visual aesthetic of the live show that relies on the collaboration of two key components: the documentary approach of the British filmmaker Adam Curtis – who sees himself as an “optimist amid dystopians”[1] – and his skilful use of the BBC archive; the GANs (generative adversarial networks) and Deepfake (a technique for human image synthesis based on artificial intelligence) of German artist Mario Klingemann, a pioneer in the field of neural network in the arts.

A one-hour and 40 minute long, consistent, bleak and conscious narrative, no greatest hit show, no acknowledgements, no encores.

But let’s proceed in an orderly fashion and, most of all, by putting aside the performance anxiety that the drafting of this article has caused since its embryonic stage due to the topics addressed – for which I believe there are more relevant experts –, and to the personal story which takes me back to that night of 1998 when for the first time I went to one of their gigs at the former Air Terminal Ostiense, at the time disused and abandoned and which today hosts Rome’s Eataly.

And it’s just that. Breaking a nostalgic, self-perpetuating loop.

I would have never believed that such vivid, though bitter, memory – we are talking about the Nineties in fact – could be “decontructed” by the Massive Attack, breaking the nostalgia trap like an endless conversation with the “ghosts of our life”[2] thanks to the simple, but rather inconvenient, truth that this constant reflection of our past is reinforced by ourselves at every click. Although convinced that certain arrhythmias of lights and combinations of dark familiar notes had the power of that involuntary memory which Proust viewed as containing the essence of the past, to my amazement and with incredible relief, I found myself living a totally different experience, free from those ghosts lurking like parasites.

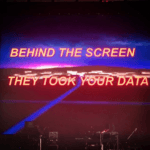

Talking about “freedom” in this context may be misleading, since it is the promise of its unlimited availability, along with the conviction that we are free to express our individuality every day, to prevent us from seeing the deceiving and dispelling use made of it.

The band’s prolific experimental collaborations with visual artists, as well as with other musicians, is well-known, moreover rumour has been fuelled recently that a famed mystery artist – whose name I deliberately avoid mentioning so weary I am of reading it – is actually one of the two members of the hit group, funnily enough, the one with a passion for visual art, that is Robert Del Naja, co-designer of the audio-visual productions.

Not only is this discussion pointless, but it is also meant to mislead the attention from some more interesting aspects, such as from the fact that in the last few years the duo has considered more relevant to join large-scale collaborative projects, with strong political implications, like the collaboration of Del Naja in 2015 on the major public artwork The Standing March with French artist JR and the filmmaker Darren Aronofsky or with Tom Yorke for the music score of The UK Gold film in the same year. And from the fact they are also aware that the traditional album package is outdated and that they did not want to embark on a world tour as a tribute to their own history, if not inspired by more poignantly serious motivations.[3]

The deconstruction of Mezzanine is fuelled by the live performance of those tracks sampled by the band in 1998: The Velvet Underground’s I Found A Reason; 10:15 Saturday Night by the Cure; the Bauhaus’ Bela Lugosi’s Dead, along with an original performance, adapted to the voice of Elisabeth Fraser, on tour with the band (even more spellbinding than in 1998), of Where Have All The Flowers Gone?, Pete Seeger’s legendary folk pacifist song and, before the closing track Group Four, a truncated cover of Levels by Avicii.

The visual aspect, on the other hand, consists of different elements: some tracks feature a brand-new interpretation of the lightning and of the on-stage LED screens typical of the band’s past concerts[4] whereas, in others the footage feature names of opioids which take shape in abstracts of contraindications, as well as of known pharmaceutical companies; Horace Andy lent again his vocals to Angel, for which the DNA code of Mezzanine[5] was screened and, for Dissolved Girl, a YouTube mashup of fan videos was created, which “play” and “perform” the track while the anonymous and daring selfie video of the “singer” is supported by the virality invading the physical space of the show.

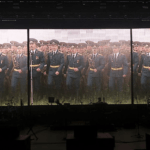

The whole project was designed together with Adam Curtis, who has a long and ongoing collaborative relationship with Massive Attack. Their collaboration for the Manchester International Festival in 2013 was mind-jarring. For the event, the Bristol-based band provided the live soundtrack to Curtis’ Everything is Going According to Plan movie, which was projected on three huge screens immersing the audience in the distinctive storytelling style of the British documentary filmmaker, who attempts to narrate our times using clips culled from the BBC archival footage, working through oppositions of time and connective linearity, where he seems to be following “a train of thought or a rich conversation between friends”[6].

If, during that gig, the presence on the stage of the Massive Attack intermittently emerged from the shadows to become part of the film itself, in Mezzanine XXI the group performs before the screens but, on most significant moments, the original audio of the video prevails over the live performance, showing that it is more than a simple concert.

This successful integration has involved a hand-in-hand collaboration with Curtis who, besides the initial videos created for the event, also designed an ad hoc video for Where Have All The Flowers Gone? and selected, together with Del Naja, quotations, phrases and images flashed on the screen to deliver a harmonious and immersive experience.

As Curtis’ documentary style is highly distinctive, the moment when Mario Klingmann’s “neurographer” work emerges, everything becomes even more prevalent. Since the release of the Artificial Intelligence program Deep Dream by Google, Klingemann has been investigating neural networks using GANs, a special class of Artificial Intelligence algorithms comprised of two neuronal networks, with one tasked to generate input images, while the other has to discriminate between fake and real images. This is the phase where the machine is trained to predict and judge new input data. If, on the one hand, the work of Klingemann and his selection of the image to create autonomous pieces that may earn their place in the art world, remind of the frottage technique developed by Max Ernst and, therefore, with an entirely human ability to recognize and find a meaning also in abstract shapes (a capability also very dear to Leonardo), on the other hand, the artificial resulting portraits are often compared to Francis Bacon’s work, particularly when he represents faces and bodies. Klingemann, however, is not interested in the creation of fakes, but rather in remaining in an in-between territory that still allows the human eye to distinguish fake images, so the warning against the potential danger of this tool resonates powerfully.

Contacted by the band, Klingemann has “trained” GANs based on data sets that Robert Del Naja compiled for the project. The result becomes visible in the track Inertia Creeps where, behind the disturbing face that enlarges, disfigures and morphs into other celebrities (such as Britney Spears), is the easily recognizable Donald Trump whose features seem to perfectly match with those of Vladimir Putin’s, both undisputed protagonists of Mezzanine XXI, as well as of the final part of HyperNormalisation, the 2016 documentary by Adam Curtis[7].

In an age where we are spectators of a bizarre theatrics of politicians and journalists, where everyone aims only to keep a strange and disturbing system afloat, and where those in charge “know that we know that they don’t know what’s going on”[8], it gives a sense of lack of dynamism. “If you liked that, you will love this” is a slogan that not only stand out on the Massive Attack’s stage, but that we often read in our emails or on the online recommendations resulting from our researches. We are victims of a machine that knows everything about our latest choices, and which therefore predicts the future exclusively based on as many repetitions of our own past. Furthermore, ELIZA – one of the first chatbot, developed at the MIT and which simulates a Rogerian psychotherapist – demonstrated it in the Sixties: the response with a rephrasing of our questions by the computer brings a sense of relief, because one feels protected by any judgment or from too emotional reactions. This type of “tranquillizer”, however, has reached a point where we feel trapped, because we are aware that, what they recommend, after all, is only the response to our researches, and that the manipulation of our preferences or states of mind is always online, even as we sleep. In the absence of a narrative and imaginative line, within our past, the only possibility is to analyze what has happened and to admit that we feel lost. Only in the loss, as Curtis underlines, ideas may newly come to light.

Manuela Pacella

[1] The antidote to civilisational collapse. An interview with the documentary filmmaker Adam Curtis in “The Economist”, 06/12/2018, https://www.economist.com/open-future/2018/12/06/the-antidote-to-civilisational-collapse

[2] Mark Fisher, Ghosts Of My Life. Writings on Depression, Hauntology and Lost Futures, Zero Books, 2014. The quotation does not refer only to the title but also to the entire essay whose reading, if interested, is highly recommended.

[3] Alessandro Zaghi, Stiamo vivendo nel futuro nero di Mezzanine. Interview with Robert Del Naja in “Rolling Stone”, 06/02/2019, https://www.rollingstone.it/musica/interviste-musica/massive-attack-mezzanine-robert-del-naja-intervista/444327/

[4] Designed together with the British art collective United Visual Artists.

It is worth mentioning the interactive sculpture Volume in 2006, collaboration between UVA, Robert Del Naja and Neil Davidge, exhibited for the first time at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London.

[5] For Mezzanine’s 20th anniversary, the band has encoded the album in a DNA spray paint.

[6] The antidote to civilisational collapse. An interview with the documentary filmmaker Adam Curtis, op. cit.

[7] The word Hypernormalisation was coined by anthropologist Alexei Yurchak with reference to the paradox in the Soviet Union during the Eighties, where everyone was aware of the situation but they could conceive of anything but the status quo, so they just accepted this sense of total fakeness as normal. In his 2016 film, Adam Curtis drew a parallel between that socio-political situation and our present day.

[8] The antidote to civilisational collapse. An interview with the documentary filmmaker Adam Curtis, op. cit.